Christobel Munson was one of six people who bought the Fowler family farm on Fowlers Lane in 1994. They transformed it from a former farm into a thriving Intentional Community Title property of 12 households. Here, she reflects on the changes.

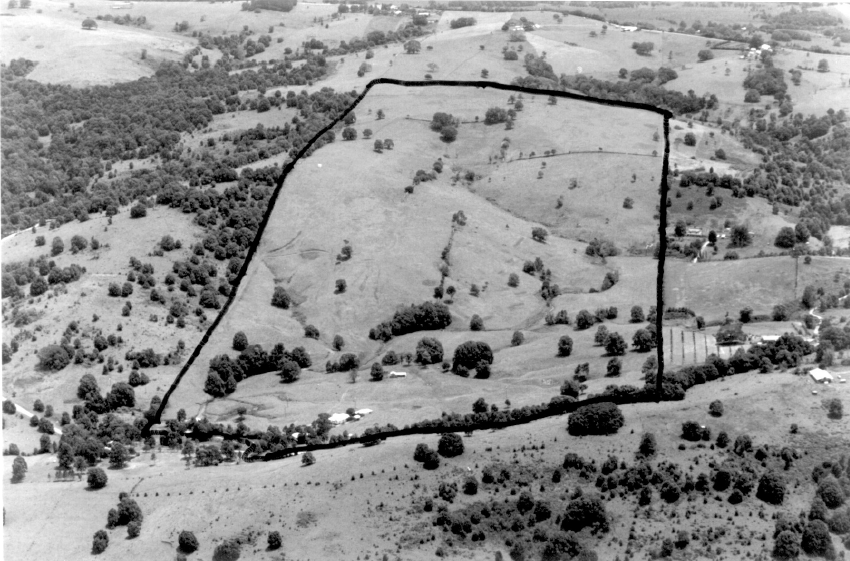

When we bought the property, Harry Fowler had been dead six years.

It seems he wasn’t any great shakes as a farmer, devoting so much of his time, enthusiasm and energy into countless worthy Bangalow community activities. Though he hadn’t kept the land looking like a workable farm, his niece and nephew, who inherited the property, spent a few years cleaning it up to make it presentable to market.

As a cattle grazing property – which is how it was marketed – it was too small for a single family to make a living from. But for our purposes, it was perfect.

It was generations since it had been a workable dairy. The land, though recently spritzed up – paddocks all slashed of weeds and the countless tonnes of rocks all gathered up and shovelled neatly out of the way and into the gulleys – looked as good as it could. But with streaks of erosion slicing through bare hillsides, to us, it seemed lifeless and unloved: it felt bleak.

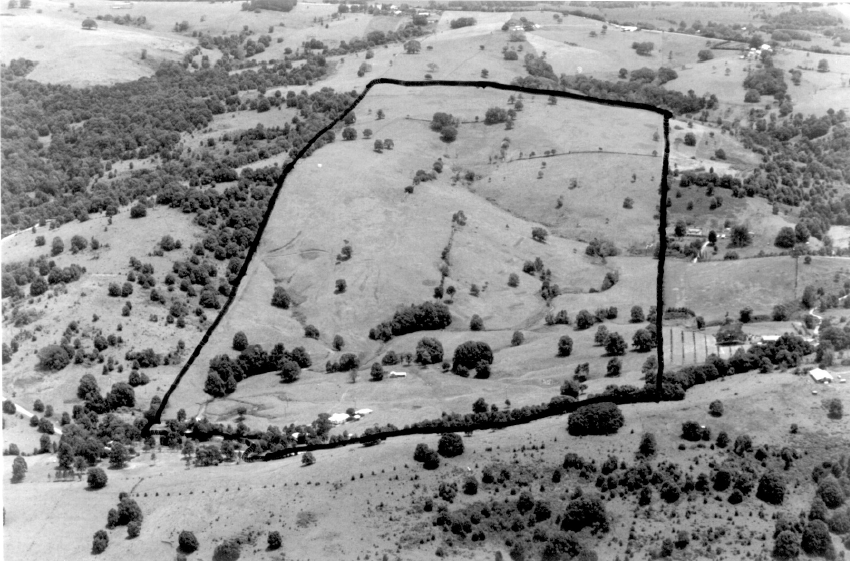

Apart from the original Fowler family farmhouse, 11 additional houses have been built over the years. Our 12 houses stand on around two acres of land per lot – each private individual bubble hanging off the internal road – and together, we care and manage the other 90 communally-owned rural acres.

Inspired by the countless consultants’ reports we had commissioned, covering every possible aspect of life on a potential community, the minute we could, we set to, to transform the land. As well as creating all the infrastructure needed before houses could be built – 1.7km of internal paved road, underground power, fencing, and heaps more – we quickly leapt in, keen to bring our dry paddocks back to life.

Setting the scene for us was an ‘Environmental Enhancement and Management Plan’ (EEMP) that we had prepared by Firewheel Rainforest Services early on. It outlined how we could potentially transform the worn-out land through environmental repair, indicating where and what we could plant: species lists tailored to select the ideal plant for every nook and cranny, whether up on the high, windswept ‘Jindibah Heights’, where nine of our houses were built, or along the frost-prone creek flats.

Our first aim was to create a fertile, thriving environment into which we could build our houses. We created privacy for each one through appropriate native plantings; these also reduced the impact of new houses on neighbouring properties. We wanted to restore rainforest along the Sleepy Creek riparian corridor, and (dare I say) “beef up” the two acres of Big Scrub we found on the far side of the causeway over the creek. We also wanted to protect and enhance the habitat of any endangered or vulnerable threatened species on site.

With the property sectioned off – on maps, at first – into zones labelled ‘Rural Living’, ‘Habitat/Regeneration’ and ‘Agricultural’ – we got planting.

In the early days, there was a rough bush track round the property, requiring four-wheel drive. As soon as construction started on the internal road, we utilised the scraped-off topsoil to plant visual screenings along the roadside, giving each potential house a thick privacy screen. These trees are now 20 to 30m high. An agricultural buffer zone was planted along our eastern border, to prevent any spray drift coming onto our land from the neighbouring macadamia plantation to our east.

Over a decade or so, each year we would aim to plant another 1,000 rainforest trees, appropriate for the site – per our EEMP. Some years, we’d attempt to plant more, and organised working bees where as many people as possible living on the land, would join with our contractor to plant that year’s quota. Today it is immediately apparent how much life all our plantings – nearly 12,000 native trees – have restored to the land. And of course we found out that controlling environmental weeds is both imperative and an ongoing, costly challenge.

A big point of difference from any other communities being established at the time, was our wish to potentially farm parts of the land, or take up any emerging agricultural possibilities. Most of the other communities at the time focussed exclusively on rainforest regeneration. We wanted to retain the option to graze cattle or whatever horticultural pursuits might work well here: we didn’t want to preclude any possibility.

On each of our house lots, owners have landscaped and planted what suited them. Some have created flat areas for kids to play on, with room for veggie plots, swings and trampolines. For others, a stunning seaview from the terraced pool, with a few strategic easily-managed feature plants, has been what’s important. To me, it’s been creating a densely planted garden which supplies food: an orchard, bush tucker, flowers, fruit.

While this property could easily have ended up as an unprofitable farm running beef cattle (as often happens when city people relocate to the country and don’t know what to do with the land), we’ve found a way that 12 households can each care for their own lot, so each garden is loved and flourishing. The trees we’ve planted on the remaining common land have brought the rest of the land back to life, attracting lush flora and abundant fauna in the wildlife sanctuary it’s become, while providing shade for the agisted cattle and horses. The creek, now shaded by mature trees, attracts us to sit, or swim, or simply enjoy nature’s bounty.

At night, I hear possums, bandicoots or echidnas, shuffling about in the jungle outside my bedroom window. Driving home in the dusk, wallabies can be seen leaping across the fields, and snakes and reptiles of all kinds, lurk throughout. On the other side of the house facing east, looking towards the sea, I watch goshawks and huge eagles, floating on the thermals. Bands of raucous yellowtailed black cockatoos, screech across the skyline on summer evenings. When I open my curtains in the morning, there’s usually a few kookaburras checking out their potential breakfast, perched high up on the stalk of the giant Mauritius Hemp.

At ground level, as I walk through the orchard to feed the chooks, past my native bee hives, blue-tongue lizards, or tiny skinks freeze for a moment, then slink on about their lives. When the chooks have left grain, the roundeared bush rats arrive for the left-overs. A series of snakes, all named Monty Python, regularly check out the rat situation from the roof of the nesting boxes in my chicken coop, conveniently taking care of excess numbers. Other snakes have found their safe and happy place in the 300 metres of rock wall, built along a section of our internal road. Everyone’s happy.

It’s been an interesting 30-year transformation.

*This is an extract from a book Christobel is writing on the conversion of the former dairy farm into an intentional Community Title property.