The story of how Abracadabra came to be, 50 years ago this year, paints a picture of a very different time in an almost unrecognisable place. “Terminal to trendy,” laughs proprietor Hamilton Du Lieu of the transformation he has witnessed the town go through over a half century of enormous change.

The story of how Abracadabra came to be, 50 years ago this year, paints a picture of a very different time in an almost unrecognisable place. “Terminal to trendy,” laughs proprietor Hamilton Du Lieu of the transformation he has witnessed the town go through over a half century of enormous change.

The 70s saw Bangalow very down on its luck. “Everyone said it was a dying town,” he explains. Hundreds of semi-trailers barrelled through the main street each day, scraping awnings, rattling buildings and making it difficult to cross. Some storefronts had people living in them. Others sat empty. His daughter Rebecca remembers playing ‘shops’ in one where the proprietors had simply walked out, leaving everything behind.

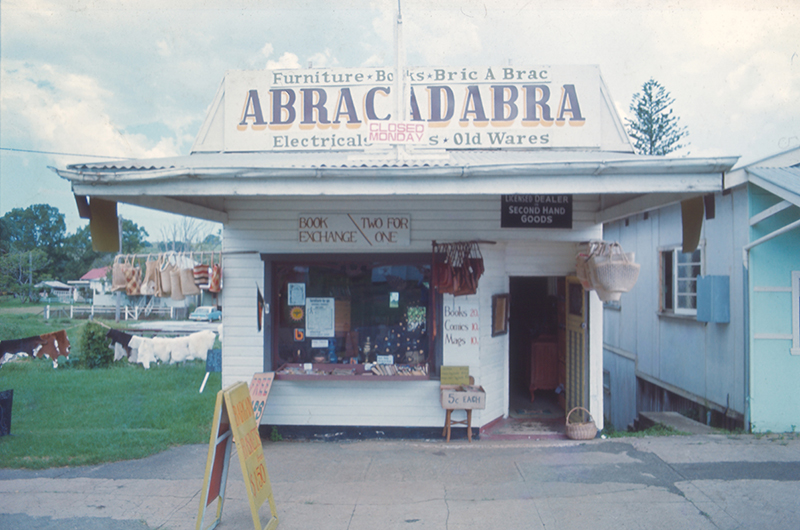

The Du Lieus and their three young daughters had been storing their furniture for a couple of years after relocating from Sydney in 1970, when a friend suggested renting a shop in Bangalow for half of what they were paying. They leased the old butcher’s shop and stowed their belongings, but in 1973 the owner announced he didn’t want to rent it anymore and offered to sell for $2,000 – the equivalent of just under $23,000 in today’s money. And abracadabra alakazam, a Bangalow institution was born, responsible for giving the region a 30-year-long catchy TV campaign and generations of local teenagers their first job.

Initially a bric-a-brac, book and old-wares dealer selling stock sourced from clearing sales and auctions, Hamilton asked the petrol station next-door if he could park on their land. To his surprise, they informed him he’d bought the vacant lots around the old timber building too – gaps left by the 1931 fire which took out that row of shops, including the original Bangalow Herald whose charred stumps remain beneath the floor today. Leaking like a sieve and sinking into the ground, Hamilton describes it as a “shockingly bad building,” built by unskilled labour during the Depression with timber salvaged from the old butter factory.

Old wicker washing baskets from clearing sales were always quick to sell, giving Hamilton the “light bulb” moment of sourcing baskets. They burnt incense to mask the musty smell from the leaks, upsetting passers-by who assumed it was marijuana and crossed the highway to avoid inhaling it. “When we realised people were offended by it, we thought ‘great!’, and started selling that too.” Apart from “You sell smokes?”, the number one question Hamilton was asked was “Why on earth are you here?”. As the original “odd people” they were met with suspicion, and even “thoroughly investigated and surveilled” as a possible channel of drugs into the region.

But Hamilton was on a mission to further transition away from his career in advertising and spend more time with his family. As a young copywriter in London working for a transnational agency, he was sent to Sydney in 1963 for a year “to show the Australian end how to do ‘proper advertising’”. Shocked to find the Australians doing just fine, and that everything was not trying to kill him, they soon realised they had been “comprehensively lied to about how primitive and dangerous the country was”. The Du Lieus decided to stay.

He spent the next seven years at a Sydney agency managing high-profile asbestos, airline, alcohol and tobacco accounts, but as well as never getting to see his family, he grew increasingly uncomfortable with what he saw as his role as a “merchant of death… everything I specialised in killed people”. They headed north “with no prospects or thought,” living in a rudimentary shed on a banana farm at Middle Pocket, owned by a colleague’s wife’s family. He was soon in high demand as a freelancer, particularly as a jingle-writer for car dealers in Brisbane, who ferried him by light aircraft from the Tyagarah airstrip.

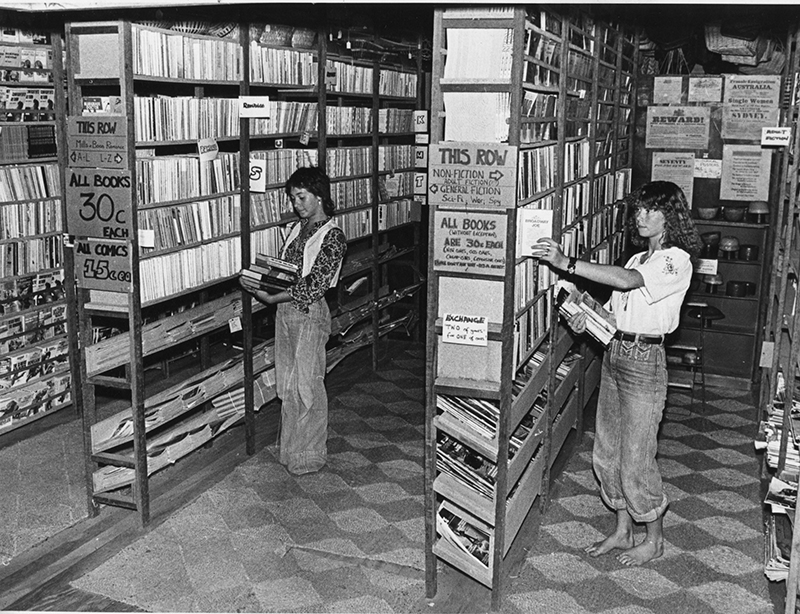

The shop unconventionally opened only on weekends in the early days. “People would go for Sunday drives and nowhere else was open.” But it was tough going. “All the money I earned during the week, I lost on the weekend,” he smiles. Undeterred, they rolled up their sleeves and self-built the ‘Book Barn’ and former hair salon on the eastern half of the site, later adding the warehouse and residence out the back. Most of their deliveries arrived by train to the Bangalow station, and semi-trailers of books and comics, diverted from being pulped, were unloaded at the A&I Hall and sold two-for-one at 20 cents.

L to R: Alice Bewick, Paula Bannatyne, Tanya Jacek, Kathy Shultz, Linda Shultz, Sonya Jacek, Tracey Bulmer, Rebecca Du Lieu, Jane Flick, Joanne Jarrett, Joanne Solway

Hamilton’s iconic 1981 ad might be the “cheapest commercial ever made,” laughs Rebecca, who features in the ad herself and still works in the store today, now alongside her daughter Sophie. For the ad, the letters ‘Abracadabra’ were cut out of felt and pinned to the yellow t-shirts worn by a line-up of local young women bearing famous Old Bangalow names such as Jarrett, Solway and Flick. (The ads, along with a treasure-trove of historic photos of the shop and town can be found on the Abracadabra website.)

The 1994 highway bypass was the genesis of many new businesses, with Abracadabra serving as an inspiration. “People figured if a basket shop like mine could make it, they could too,” says Hamilton. He’s watched as waves of shopkeepers from capital cities have passed through – lots of “black and white” from Melbourne, “country-style” from Brisbane, and “kind of raffish ones” from Sydney. Asked how he feels about the gentrification of the town, he is full of enthusiastic praise for all the “smart and lovely” people that have enriched the community. He still lives out the back, making the “big commute” across the deck each day.

Customers often reminisce about growing up with the jingle, or bring in their grandchildren to show them their favourite shop from when they were little. “That’s one of the things that can happen in 50 years,” he says, gesturing at Rebecca, “even your youngest daughter can become a grandmother”. Hamilton’s great-grandsons attend Bangalow Public, and, along with his penchant for early mornings, are the driving force behind the rather unconventional new opening hours of 5:30am to 2pm (12pm on weekends). “Afternoons are for family time,” he explains. While the early mornings might not be particularly busy, he says he’s “not a fan of busy,” and his morning visitors are among some of the “best people in the world”. “Broadly speaking, we’re not about making money, we’re about having fun.” When asked about his plans for retirement, he is characteristically unorthodox in his attitude. “I don’t work, so how can I retire? You can’t retire from fun!”

Georgia Fox